By Robert A. Vella – June 20th 2024

Recently, I had an intriguing conversation with a local barista friend of mine. She told me that the homeless issue in our town is getting out of control, and that her employer plans to put up “No Loitering” signs to hopefully reduce the increasing petty theft and personal safety problems. That sparked a larger debate about what’s going wrong in America today.

I asked her what was causing it, and she suggested rising mental illness. I asked her what was causing that, and she appeared dumbfounded.

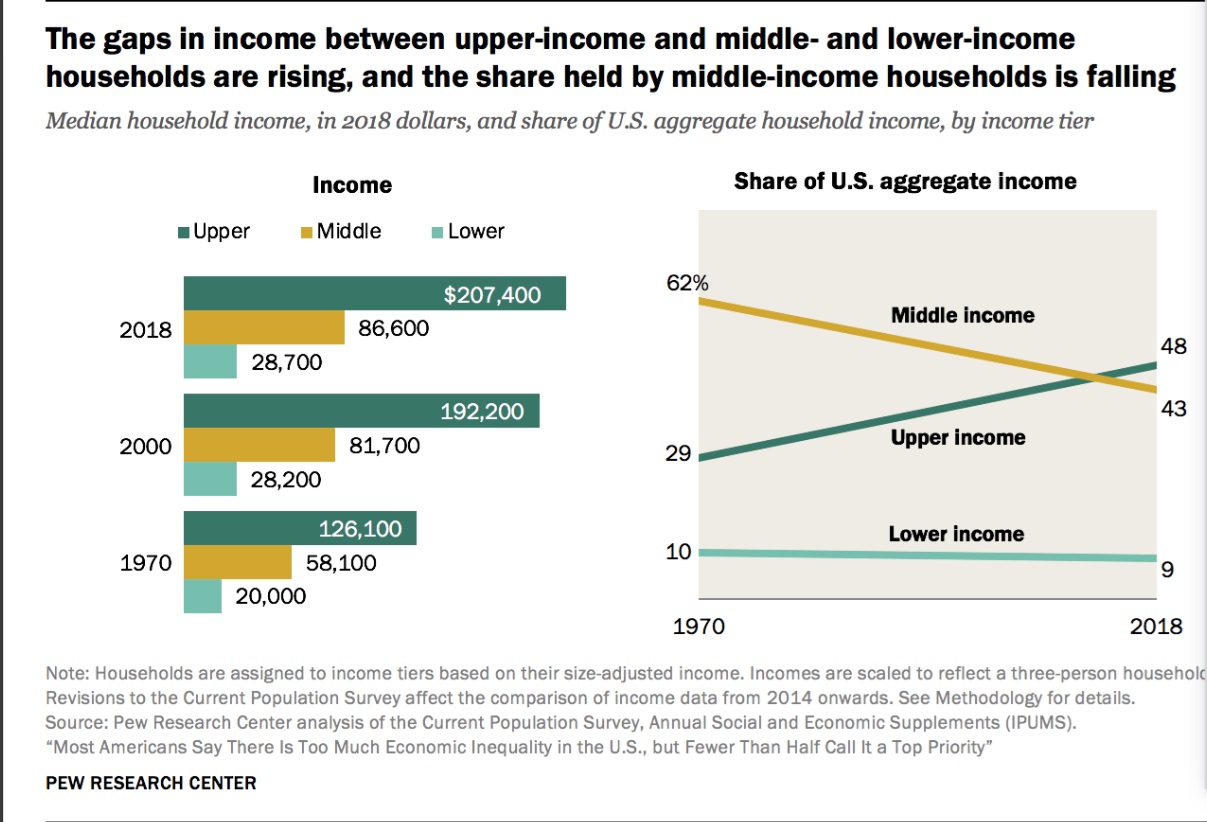

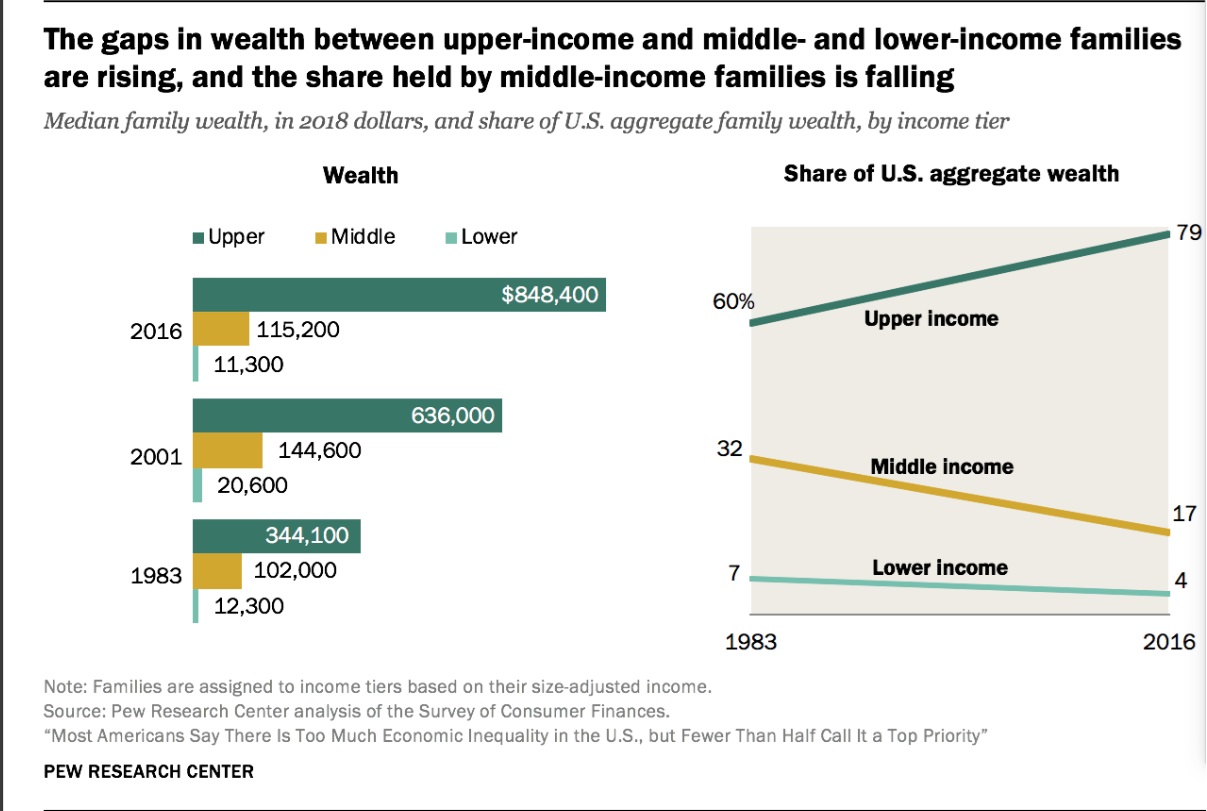

I told her of my experiences in the early 1970s when I became an adult. Back then, the hippie movement was still prevalent in which young people “dropped-out” of society and chose to live free off the land instead of conventionally working for a living. Except for them, the number of homeless people and the societal consequences of homelessness were relatively small. The vast majority of people who wanted to work could find employment in a wide variety of jobs which generally paid livable wages. Labor unions were strong, family-owned and small businesses dominated the local economies, and manufacturing industries operated regionally where unskilled workers could learn a trade. The middle class thrived, typically owned their own homes, and usually had enough money to send their kids to college if desired. Yes, there were rich people then too; but, the wealth gap was many times smaller than it is today. Yes, there were impoverished ghettos in large cities; but, that resulted much more from systemic racism than it did from the general economic conditions.

Now, the middle class has shrunk dramatically, labor unions have been greatly weakened, median income has fallen while the wealth gap has swollen to perverse levels, home ownership is becoming an unrealistic dream, college education has already become unaffordable, and the homeless population is expanding nationwide. I don’t believe one needs to have earned a PhD in psychology to appreciate the relationship between these impactful societal stresses and mental health. This rise in mental illness, exacerbated by the psychological effects of addictive social media use, is quite understandable.

The barista (a very smart and pleasant person, by the way) rebutted that government is not going to solve those fundamental social problems and that local community organizing would be a more practical approach. I agreed (with reference to corporatism in which the “body politic” – i.e. polity – is captured by monied interests), but expressed my doubt that any localized action could even begin to redress those far larger issues afflicting our country. At that point, the conversation ended.

Is it true that the federal government of the United States is unable to reverse these disturbing trends which have transpired over the last 4+ decades? Well, considering its current highly polarized and dysfunctional political state, I would say that government is unwilling to do so. For democracy to work properly, it requires either a sufficient majority or a cooperative coalition. What we have now is the polar opposite, one political party which is desperately trying to defend our constitutional republic and an opposing party (of roughly equal numerical size) which is fervently trying to supplant it with an autocratic authoritarian regime.

However, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that America’s government was in a more functional political state. Would it still be unable to solve our seemingly insurmountable problems? The answer to that question can be found in the past. During Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, the U.S. government successfully led the country out of the existential crisis of the American Civil War and – in the process – abolished slavery. During Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency, the federal government saved the nation from two more concurrent existential crises – the Great Depression (the world’s worst economic disaster in modern history) and World War II (in which fascist totalitarianism nearly conquered the world). During Lyndon Baines Johnson’s presidency, the government ended Jim Crow segregation in the southern states and established the legal status of racial equality nationwide with the passing of the 1964 Civil Rights and 1965 Voting Rights acts. If government can solve those monumental problems, then it certainly can solve – or, at least mitigate – the profound socioeconomic imbalances which are triggering the stress-induced maladies worsening in America today.

An additional historical example also proves that government is capable of causing great harm whether intentionally or not. When hardline Republicans swept into power in January 1981 with the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan, they moved quickly to dismantle the acheivements of their most despised ideological foe – the successful progressive policies enacted from 1933 to well into the 1970s. This new political movement (which also allied similarly frustrated Christian fundamentalists and white supremacists) was sparked by one influential man in 1971, from: The Powell Memo: A Call-to-Arms for Corporations

In corporate circles, this pronounced and sustained shift was met with disbelief and then alarm. By 1971, future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell felt compelled to assert, in a memo that was to help galvanize business circles, that the “American economic system is under broad attack.” This attack, Powell maintained, required mobilization for political combat: “Business must learn the lesson . . . that political power is necessary; that such power must be assiduously cultivated; and that when necessary, it must be used aggressively and with determination—without embarrassment and without the reluctance which has been so characteristic of American business.” Moreover, Powell stressed, the critical ingredient for success would be organization: “Strength lies in organization, in careful long-range planning and implementation, in consistency of action over an indefinite period of years, in the scale of financing available only through joint effort, and in the political power available only through united action and national organizations.”[3]

[…]

Powell, Harlow, and others sought to replace the old boys’ club with a more modern, sophisticated, and diversified apparatus — one capable of advancing employers’ interests even under the most difficult political circumstances. They recognized that business had hardly begun to tap its potential for wielding political power. Not only were the financial resources at the disposal of business leaders unrivaled. The hierarchical structures of corporations made it possible for a handful of decision-makers to deploy those resources and combine them with the massive but underutilized capacities of their far-flung organizations. These were the preconditions for an organizational revolution that was to remake Washington in less than a decade — and, in the process, lay the critical groundwork for winner-take-all politics.

So began the long and continuing neoliberal era of deregulation, corporate consolidation, the economic and political empowerment of wealth, the subjugation of workers and consumers, and the demise of the once-prosperous middle class, which slowly but surely brought America to this precarious moment in time. Although hardline Republicans were the driving force behind it, moderate Republicans and centrist Democrats (e.g. Bill Clinton) fell in line with the movement too because they soon realized that the path to political power now depended upon the financial support of Big Business and no longer upon the will of the people. In effect, democracy was usurped. As the social deterioration developed systematically, displaced blue-collar workers (from the relocation of American manufacturing to foreign countries which most severely impacted the Midwest Rust-Belt states of Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) became enraged and susceptible to right-wing political propaganda which conveniently redirected their primal hostility towards immigrants and ethnic minorities (from the playbook of fascism). This was how the megalomaniac Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016. His opponent, Hillary Clinton, was precisely the kind of establishment candidate that the disaffected hated most.

That is how we got here. It didn’t just happen accidentally. It was deliberately planned. Whether or not the perpetrators anticipated, or even wanted, the destruction of American democracy (which is now imminent) remains an open question. Perhaps an answer isn’t necessary… because they risked choosing a radical course of action regardless of the cost.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Concentration of power in a small number of big companies is not, itself, new. Corporate concentration has grown significantly in recent years, bringing with it increased corporate profits and a falling share of income going to workers, researchers have shown. In addition, corporate capital investment has slowed and so has the rate of new business formation.

Scholars have debated why all of this has happened — new technology, the decline of worker bargaining power and the failure of antitrust authorities are all said to be causes — but the facts themselves are stark.

Nor is it news that high equity values fuel corporate acquisitions or that large companies like to snap up small ones. The economists Colleen Cunningham of London Business School, and Florian Ederer and Song Ma of Yale have shown that bigger companies engage in “killer acquisitions” buying innovative competitors to prevent them from becoming major threats. My colleague Thomas Wollmann at the University of Chicago, in work that includes the perfectly titled “How to Get Away With Merger,” has shown how health care companies try to keep such consolidations below the radar screen of regulators.

What is unusual at this moment is the extreme divergence in the health of different types of companies: Many of the biggest are flush with money, while smaller competitors have never been in more precarious shape.

In the United States, the number of homeless people on a given night in January 2023 was more than 650,000 according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[3] Homelessness has increased in recent years, in large part due to an increasingly severe housing shortage and rising home prices in the United States.[4][5]

Historically, homelessness emerged as a national issue in the 1870s.[6] Early homeless people lived in emerging urban cities, such as New York City. Into the 20th century, the Great Depression of the 1930s caused a substantial rise homelessness. In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the homeless population of the country to be 228,621 (or 0.09% of the 248,709,873 enumerated in the 1990 U.S. census) which homelessness advocates criticized as an undercount.[7][8][9] In the 21st century, the Great Recession of the late 2000s and the resulting economic stagnation and downturn have been major driving factors and contributors to rising homelessness rates.

The main contributor to homelessness is a lack of housing supply and rising home values.[4][10][11] Interpersonal and individual factors, such as mental illness and addiction, also play a role in explaining homelessness.[10][11] However, mental illness and addiction play a weaker role than structural socio-economic factors, as West Coast cities such as Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles have homelessness rates five times that of areas with much lower housing costs like Arkansas, West Virginia, and Detroit, even though the latter locations have high burdens of opioid addiction and poverty.[11][12]

You must be logged in to post a comment.