By Robert A. Vella

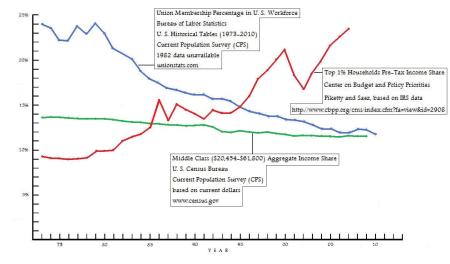

In 2011, I statistically linked the cause of middle class decline in the U.S. to a precipitous drop in union membership brought about by bipartisan support for neoliberal economic policies. Here’s the plain-as-day graph I published:

Five years later, mainstream economists are now seeing the light.

From The American Prospect – As Union Membership Declines, Organized Labor Focuses on Nonunion Workers:

In an election season dominated by populist appeals, globalization and trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership have come under fire for offshoring the manufacturing jobs that helped create a healthy American middle class. But there has been less attention to another factor that has contributed to the increase in income inequality: The dramatic decline in union membership since the late 1970s.

A new Economic Policy Institute white paper published Tuesday found that since 1979, the share of men who belong to unions in the private-sector workforce has fallen from 34 percent to 10 percent.

According to the Washington-based think tank, if unions had the same presence in the private sector today that they did in 1979, men—both union members and nonunion members alike—would be making $2,704 more each year. The EPI researchers also found that union membership makes a tremendous difference for people who do not have college degrees. Real wages for nonunion men without a college degree are even lower today than they were in the 1970s. (As for women, the report noted that “the effects of union decline on the wages of nonunion women are not as substantial because women were not as unionized as men were in 1979.”)

Jake Rosenfeld, an associate professor of sociology at the Washington University in St. Louis, is careful to note that the loss of traditional union manufacturing jobs has contributed to the decrease in union membership. But Rosenfeld, a co-author of the EPI report, also says that “you can’t overlook the role of employer opposition” in that decline, especially as organized labor tries to broaden its reach to other sectors like the service industry.

“It became part and parcel to the way of doing business starting in the ’70s and ’80s,” Rosenfeld says. “Employers got organized and became incredibly effective at using the regulations to rid themselves of existing unions and prevent new unions from coming in.”

From The Atlantic – Fewer Unions, Lower Pay for Everybody:

Today’s wealth inequality is, in a sense, a return to the Gilded Age. In 1928, the economic divide was large: The bottom 90 percent of Americans earned 50.7 percent of all pretax income, while the top 1 percent earned 23.9 percent, according to research by Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. The Great Depression and World War II acted as equalizers, and by 1944, the bottom 90 percent earned 67.5 percent of income, while the top 1 percent earned just 11.3 percent.

But that relative equality started to morph again in the 1970s and by 2012, the bottom 90 percent accounted for just 49.6 percent of all pretax income, while the top 1 percent held 22.5 percent.

There are plenty of theories about what caused this reversal: It could be that globalization made it easier for companies to offshore the type of jobs that once paid a good wage in America. Or maybe technology is to blame, as machines replaced physically demanding and repetitive jobs that once employed blue-collar workers. A third theory, supported by Saez himself, argues that declining top tax rates for the very rich allow them to earn more and save more money, creating a vast and growing income gap. But there’s another factor that isn’t often addressed by the above theories, which is the role that rules and regulations governing the minimum wage and unionization have played in eroding the middle class.

Indeed, since 1979, the percentage of U.S. private-sector workers that are unionized has fallen to 10 percent, from 34 percent. Unionization among men without a college degree has fallen to 11 percent from 38 percent in 1979. And that, in turn, has led to some pretty compelling changes in the way workers are compensated, and the power they have to influence their earnings. “Policies regarding unions and the minimum wage are going to affect the wage structure, such as how much of the value of the company makes have to be given to workers, especially low and middle pay workers,” Saez told me in a phone call earlier this month.

To compliment your insightful post, Michael Lind, a historian and native Southerner states in his book “Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States”, that “Southernomics,” an economic policy honed in the Old South, is spreading across the United States. He calls this process the “Southernization” of the American economy.

He states that their strategy is the same as that of the 19th century Southern elite — weaken workers’ power and lure corporations with promises of low taxes and minimal regulation.

“Every Southern state is a “right-to-work” state, which means it has laws that make it more difficult for unions to organize.

As I’ve mentioned many times before, the South has the worst quality of life according to numerous studies and data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Lind further states that those who are nostalgic for the Old South may finally be able to fulfill at least some parts of the famous vow made by defenders of Southern heritage.

The South will rise again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apropos. Whether the actual form is oligarchy, plutocracy, or any other authoritarian system, it produces the same result – the rebirth of aristocracy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person